by the Rev Theodore Lewis

In itself the Anglican Consultative Council meeting in Lusaka (ACC-16), was reminiscent of a bowl of blanc mange without a bottom. To be sure, the meeting adopted some 45 resolutions and elected a new chairman. But none of the resolutions mattered much; and the new chairman, the Archbishop of Hong Kong, is reportedly cosy with Beijing. Negatively, however, it allowed The Episcopal Church (TEC) delegates to participate fully, including with regard to doctrinal matters. It thereby failed to uphold the three-year suspension of TEC resolved on by the Primates’ meeting in Canterbury last January, in consequence of TEC’s canonical allowance of same-sex marriage. And this has two major significances. One is that Justin Welby, the present Archbishop of Canterbury, who is president of the ACC and was understood by the Primates to give assurances of TEC’s doctrinal non-participation, can be relied on little more than his predecessor, Rowan Williams, to play a positive role the Anglican Communion. The other is that the GAFCON Primates’ and their associates, though not uncoordinated in confronting Canterbury’s negativity, need to coordinate much more. Conciliarism points to a way in which they might do so.

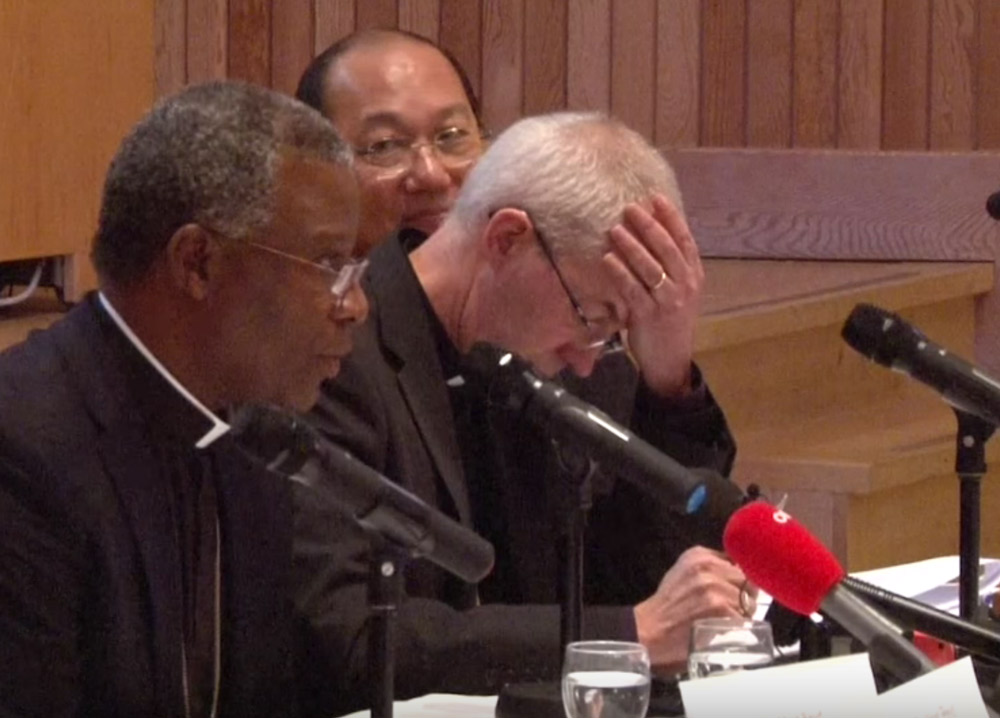

Still Welby remains a major player in the Communion. Accordingly it would be well to ascertain how he has squared the assurances he gave the Primates with what eventuated at ACC-16. For this will cast light on his frame of reference, in terms of which he will need to be dealt with. In this connection his three addresses bearing on the Primates’ meeting are significant: (1) to February’s General Synod of the Church of England, (2) to ACC-16 as its president, and (3) to ACC-16 in reflecting on the Primates’ meeting. Taken together they bring out his remoteness from the Jerusalem Declaration— in another thought-world. They bring out also what is at best his theological unsophistication and at worst his theological incoherence.

In his General Synod address Welby speaks of TEC’s change of its marriage canon as occasioning or at least hastening the Primates’ meeting. He speaks also of actions—i.e. TEC’s canonical change—as having consequences. And with regard to walking together he appears to recognize that the Primates’ unanimous vote to do so was premised on TEC’s compliance with its three-year suspension. So far he seems within the ambit of the Primates’ resolution. But in its conclusion he shifts to discussion of a trio, namely freedom, order, and human flourishing, to be considered along with Scripture, tradition, and reason, not sourcing the former except “as set out by Tim Jenkins in an article in 2002.” And in so pairing the trios, he goes off orthodox rails. For without Scripture as interpreted by tradition and reason, it is not possible to know in what freedom, order, and human flourishing consist. Moreover, he runs up against Karl Barth’s dictum that any source of knowledge of God and his nature set alongside scriptural revelation inevitably takes over from Scripture. Consonantly with this, Barth holds that the only true freedom is freedom to serve the Lord.

In his presidential address to ACC-16 Welby says little directly about the Primates’ meeting. Instead he speaks of religiously motivated violence and climate change as the two main actors confronting the world and the church today. Certainly these are serious matters. But he has hardly anything to say about them that could not be said by a Unitarian. And again in the absence of Scripture, the energy as well as the insight to contend with them will be lacking.

In his reflections to ACC-16 on the Primates’ meeting, he reverts to his freedom-order-human flourishing trio. Mostly, though, this is to say that the right balance among them was what the Primates’ at their meeting were mainly concerned with. They might be surprised to learn that this balance, rather than TEC’s canonical change, was what was on their minds. More to the point is the justification he gives for his meagre follow-up of the Primates’ resolution. He begins by saying that their meeting has no legal authority over provinces and that, further, no Communion Instrument can legally bind any other Instrument. Thereby he seems to absolve ACC-16 from failure to respect the Primates’ prescriptions while leaving each Instrument free to go its own way. He does not however mean them to be incoherent. Instead, “the Anglican Communion finds its decisions through spiritual discernment in relationship.” But in attributing this possibility to such mutuality he is being romantic rather than realistic. So walking together can work given a willingness to abide by the outcome of “reception”—he cites the case of lay presidency and its non-reception—but not when a province is unwilling to await the outcome and goes ahead with its innovation anyway, as TEC has done. And to countenance such conduct, as Welby appears to do, is to walk together not in love but in indifference.

Finally by way of justification of his above meagre follow-up, he indicates that he was responsible to the Primates only for the appointment of a task force to work out how to walk together, which he has done, and for hoping that ACC-16 would contribute to the process. As for “consequences” for TEC, he now makes no mention of them.

So, if in connection with the Primates’ meeting Welby has played a less than positive role, and if his theology indicates that he is incapable of one anyway, should we simply disconnect from him? I think not, for in solving some problems that would likely lead to others. A better model is afforded by the British monarchy in its transition from preponderant authority to Parliamentary supremacy, with GAFCON and its associates becoming the equivalent of Parliament and Canterbury reduced to a largely ceremonial role. This of course would require much more unity and coordination than they have manifested in connection with ACC-16. To be sure, the provinces of Uganda, Nigeria, Rwanda, and by intention Kenya announced that they would not send delegates to ACC-16. But they did so serially rather than in conjunction and evidently were followed only by the Egyptian Archbishop, Mouneer Anis.

Still the January Primates’ meeting afforded a vision, even if fleeting, of what the Primates when authoritatively gathered in council could achieve. In gathering in Canterbury even as they did, they recalled the concliarism which has been vital in the history of the church, from the Council of Jerusalem in Acts 15 through the Council of Nicea and on towards the present. Anglicanism itself has seen a conciliar movement, starting with the Lambeth Conference in 1867 and extending to the ACC in 1968 and the Primates’ Meeting in 1978. Its apogee was the 2007 Primates’ Meeting in Dar-es-Salaam, calling for definite assurances from TEC regarding its innovations. Rowan Williams undercut them, however, and proceeded likewise to undercut the Lambeth Conference and the ACC. Now Welby turns out to be disinclined to reconstitute the movement. But in the above January vision the GAFCON Primates and their associates could find encouragement to develop a Primates’ Meeting not subject to Canterbury’s convening, thereby countervailing Canterbury. To extent that they do, Welby will have fostered conciliarism, albeit unwittingly. Further, GAFCON will have lived into its contention that “we are not leaving the Anglican Communion; we are the Anglican Communion.”

The Rev. Theodore L. Lewis is Resident Theologian at All Saints Church in greater Washington D.C.