The decision announced Friday that the Global South bishops will sit during Holy Communion during all of Lambeth’s Eucharistic services sent shock waves through the Anglican Twitterverse. It was bold. It was clear. It was divisive. But is division truly a bad thing? It is often assumed that it is, in all forms and at all times. To say it can actually be good is controversial. Archbishop Justin Welby stated at Lambeth that “division doesn’t matter,” that essentially, you can disagree and yet still be united. At other times he called division downright unacceptable and wrong. But the scriptures and reason point to the reality that often division, if not an end in and of itself, is good if it leads to a greater good: true unity.

This true unity is both created by and expressed through Holy Communion. It is a unity set in “one faith, one Lord, one baptism.” Certainly Abp. Welby would say all these things are true of the various churches together at Lambeth, that Communion should be taken by all because, despite our disagreements, we do share one faith, we do have one Lord. But can those bishops who worship with Muslims or engage in pagan ceremonies or deny the physical resurrection of Christ be said to worship the same Lord as those who hold to a biblically orthodox view of God? Or can those who deny the validity of the Scriptures or the Creed or who allow for sexual immorality in the Church be said to hold the same faith as those who continue in orthodox dogma and praxis? Reason would say no. At times one has to wonder how much reason is left in Canterbury.

If our faith can be expressed only by the most minimal of qualifications, what was the point of synods and councils in the Church’s past? Why all the effort? Would Sts. Peter and James have had to facilitate a disagreement between Jews and Gentiles at the Council of Jerusalem? Why wouldn’t St. Paul simply accept Judaizers along with orthodox Christians, saying that, though they believed different things, they were really all one? What was the point of the Ecumenical Councils? Should the Arians and the orthodox simply have communed together? After all, both parties called Jesus “Lord.” They both believed He was divine. They just disagreed on how divine he really was. So much fuss, when all this time we could have just been communing together, like one big messy family, knowing that the Holy Spirit would sort it all out eventually.

The Church’s struggle to be truly one over her history is the struggle to partner with God to become like God, that we would be one “even as Christ and the Father are one.” Church leaders like Welby lament our divisions and our inability to accept them but still pray, every now and then, that the prayer of Christ in John chapter 17 would one day come to pass. But unfortunately for Welby, unity, like all good things, comes at a cost. It requires effort. It means leaving behind behaviors separating us from life in Christ, changing our minds about false beliefs, and engaging the difficult conversations that may end up separating us from unrepentant and disruptive people.

Holy Communion is the outward sign of this inward and spiritual reality. It reflects our unity and, at times, pushes us to deal with our disunity. Divisive as this is, it is necessary for our growth and health. “Good disagreement” or “good division” should lead to purification, repentance, and restoration, unlike Welby’s “good disagreement.” As gatekeepers and shepherds of the Church, leaders are called to facilitate this process and help move the souls they safeguard through division and towards greater unity. The Lord himself, along with the apostles, didn’t seem to have a problem with division per se, as long as it led towards repentance and truth.

“Do not think that I came to bring peace on earth,” said the Lord. “I did not come to bring peace, but a sword. For I have come to set a man against his father, a daughter against her mother, and a daughter-in-law against her mother-in-law; and a man’s enemies will be those of his household.” (Matthew 10:34-36). He said this in the context of the Gospel and the offense that His name and message would cause in the world. As unpleasant as that sword may be, it is the reality we have to deal with. Christ unifies but first he divides. By His very nature He is divisive to us because truth, by its very nature, is divisive. And He is Truth.

St. Paul also refused to shy away from division in his letter to the Corinthians. After a discourse on Holy Communion and the sins plaguing the Church, he writes, “whoever eats this bread or drinks this cup of the Lord in an unworthy manner will be guilty of the body and blood of the Lord. But let a man examine himself, and then let him eat of the bread and drink of the cup.” (1 Cor. 11:27-28). Here we see a call to self-examination and the ability to manage oneself wisely before the Lord, even if that means excluding yourself (albeit temporarily) from the rest of the congregation.

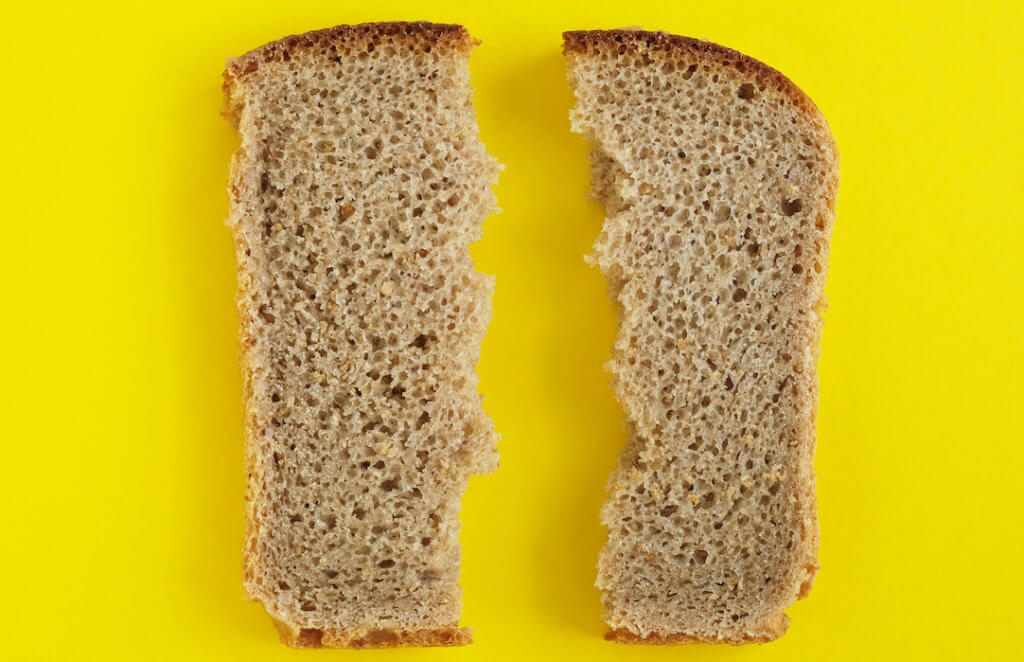

Earlier in the letter he writes these words: “It is actually reported that there is sexual immorality among you,” which begins a section on another kind of division, that which is put upon an individual from above. St. Paul calls for the Church to “expel the immoral brother” from among them. What is the purpose of this divisive act? That the congregation may become “a new unleavened batch,” free from sin, “not with the old bread leavened with malice and wickedness, but with the unleavened bread of sincerity and truth.” He continues, “I am writing to you that you must not associate with anyone who claims to be a brother or sister but is sexually immoral or greedy, an idolater or slanderer, a drunkard or swindler. Do not even eat with such people. What business is it of mine to judge those outside the church? Are you not to judge those inside? God will judge those outside. Therefore, ‘expel the wicked person from among you.’” (1 Cor. 5:9-13) These strong words no doubt imply excommunication. It is no longer a self-imposed separation but one imposed by those who guard the whole flock from those who would destroy it. And yet, in the second letter to the Corinthians, St. Paul writes about the restoration of that very same brother who was excommunicated, and we see that, even here, division can set boundaries meant to benefit not only the flock that is “orthodox” but also the individuals who are not. It withholds spiritual food so that the hunger of those separated ones might grow until they reach again for the Lord they abandoned.

The safeguarding of true Christian unity, expressed through the Eucharist, protects the faithful. It protects us from a life devoid of self-examination that can lead to spiritual laziness, sin, and judgment. It protects us from others who are harming the Church through false teaching and sin and protects those individuals from themselves. It protects us from “walking together” under the illusion of unity, eating together without ever caring to look deeper into who we are, what we believe, and why we believe it. It protects us from avoiding real and truly “good” disagreement, which is disagreement that actually leads to resolution and real change. A far cry from the weaponization of the Eucharist, the Global South bishops’ stance is a call to bring this protection to the Church, to refuse to say through the Sacrament “peace, peace” when there is no peace. Only then can the Anglican Communion move through division and towards unity in spirit and in mind, that we may be one, even as He is one.

Read an excellent article on the so-called weaponization of Holy Communion, written by our UK friends at Anglican Futures. Visit their blog for other commentary on Lambeth and the Anglican Communion at anglicanfutures.org/blog.

For a deeper historical and theological study of why Eucharistic Discipline is well within our reformed catholic Anglican practice, we commend this excellent paper by theologian Martin Davie.