Years ago when I served as a young Deputy District Attorney in California, I was introduced to the legal theory and consequences of “exigent circumstances.” Exigent literally means “emergency.” So in the criminal cases that I was prosecuting, we defined exigent circumstances as follows:

“Emergency conditions, ‘Those circumstances that would cause a reasonable person to believe that entry (or other relevant prompt action) was necessary to prevent physical harm to the [law enforcement] officers or other persons, the destruction of relevant evidence, the escape of a suspect, or some other consequence improperly frustrating legitimate law enforcement efforts.’ United States v. McConney, 728 F.2d 1195, 1199 (9th Cir.), cert. denied, 469 U.S. 824 (1984)

It was always both a question of fact and law, whether emergency conditions existed that would excuse the lack of a search warrant, knock-and-announce at the door before entering, or “Miranda” warnings before interrogating suspects. For instance, police might postpone mirandizing a suspect in order to interrogate a suspect about the location of a victim in an emergency where police believed the victim’s life was at stake. If the District Attorney could prove that those emergency conditions existed, they could overcome a suspect’s 4th Amendment rights.

So by analogy, I’d like to raise the question whether “exigent circumstances” or “emergency conditions” now exist in the Anglican Communion. The existing authorities and structures or “Instruments” of the Anglican Communion have failed to guard and uphold Biblical Christianity. The Archbishop of Canterbury, Lambeth Conference of bishops, Primate’s meetings and the Anglican Consultative Council have compromised with the spirits of the age to permit false teachers to invade the Church. The false teaching is about more than sexuality. Like all heresies that present themselves as minor teachings or disciplinary issues, they actually involve weightier matters – authority, scripture, the Gospel and who is Jesus.

Considering that fact, are there exigent circumstances in the Anglican Communion that would cause a reasonable person to believe that action was necessary to prevent spiritual harm to other persons?

I’m not the first person to raise this question. In Beyond the Reformation, Anglican theologian Paul Avis cites the Great Schism (1378-1417) to make the case that “exigent” or emergency circumstances existed in the Roman Catholic Church at that time-resulting in a formal schism- by virtue of the election of two rival Popes by the same College of Cardinals (a governing authority or structure within the Church) within a few months’ time. Avis paints a picture of the impact these “exigent circumstances” had on the Church, right down to the people in the pews:

“For the first time in the Church’s history, two popes, each with his own hierarchical structure, demanded the allegiance of Christendom. The schism produced a dual system of popes, cardinals, curia and ecclesiastical allegiances, right down to the parochial clergy. It could mean that people did not know who was their rightful parish priest, bishop, religious superior or dean of cathedral. They could not tell whose sacraments were valid. Rival candidates were appointed to important offices, such as the headship of religious houses. Each side denounced and excommunicated the other.”[1]

Avis goes on elsewhere to explain how this crisis produced a movement in the two centuries immediately preceding the Reformation, a conciliar movement that aimed to reform the Church, expunge heresy, and unite the Church by healing the breach in the papacy, “calling together bishops, lay rules and theologians in a free general council that would ultimately be above the popes.”[2] Avis makes the case that this historical development may have some principles Anglicans could use to address current schism within the Communion today.

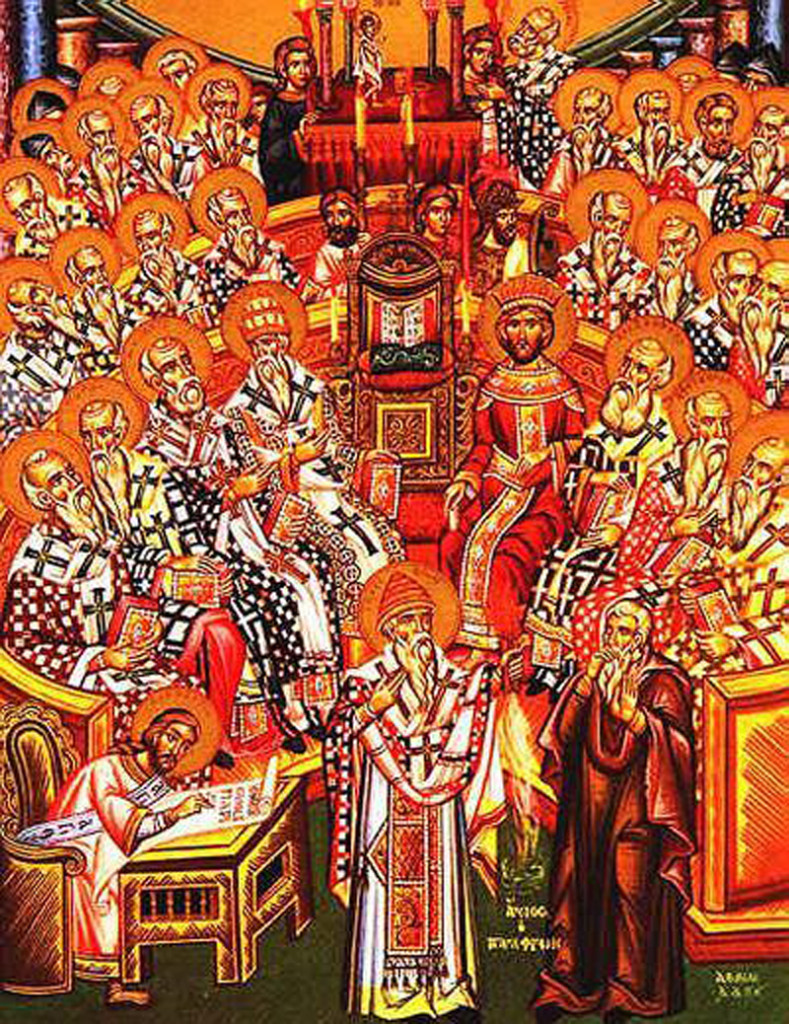

So when Bishops fail, as they did during the Great Schism, what can the Church do to right itself? Well, the Church can call a Council which represents the whole Church and all its orders (Bishops, clergy and non-ordained leaders) to take action to restore faith and order. This is in fact what happened during the Great Schism, even when Popes and Bishops could not agree to call the Council. It was at the Council of Constance (1414-1418) in the decree Haec Sancta that the great Catholic conciliarist Jean Gerson declared that exigent circumstances existed and that a free and general council of the whole Church must assemble to correct erring bishops, including a Pope and the Cardinals, and must take action to heal the schism and restore the doctrine, discipline and order of the Church.

Such a free and general council derives its authority immediately from Christ himself as representative of the universal church on the basis of the Holy Scriptures. Therefore all Christians, including the Pope and bishops, are bound to obey its decrees in settling controversies of faith, ending schism, and reforming the church.[3] Of course, as Reformed Catholics, Anglicans believe that in such councils the Church may not ordain anything contrary to God’s word, the Bible, nor “expound one place of Scripture that it be repugnant to another.” (Article 20). We also believe that the authority of such Councils ultimately rests on the authority of the Bible (see Article 21).

Let’s be honest too. If we look at the crisis of faith and order within the Anglican Communion, it’s not only bishops that are at fault. In the last 20 years, the Archbishops of Canterbury have failed to address the problems and even made things worse.

The leading bishops of the Communion of Anglican Churches, the Primates, tried to take action in 2007 and recently in January, but were stymied both times as we noted here. In their last “official” meeting in 2008, the Primates barely mustered a quorum for an insipid statement about their gathering for fellowship and prayer only—leading some to wonder why they meet at all. We were present at the Anglican Consultative Council Meetings in 2009 where we watched ACC-14 fatally weaken the proposed “Anglican Communion Covenant” through parliamentary sleight of hand, and in 2012 at ACC-15 where they refused to take any action on the Covenant. We have documented how in less than four months ACC-16 in Lusaka overturned the will of the Primates “gathering” in January. Yes, the Lambeth Conference of Bishops meeting in 1998 produced an exceptionally clear statement on Biblical, and therefore Anglican, teaching on human sexuality, marriage and qualifications for ordained leadership within the Church, in its Resolution I.10. But Lambeth 2008 “Indaba’d” the statement to death through facilitated discussions without any action—and minus almost 300 bishops who boycotted due to the presence of The Episcopal Church’s bishops.

If this isn’t “exigent circumstances” – if these facts do not add up to emergency conditions by virtue of massive structural failure and paralysis – what more could we possibly need to follow the historical precedent of the catholic conciliarists? What more do we need to call a general council of the Communion to replace its failed structures? The situation in fact is so bad that, as others have observed, it has descended from the ridiculous to the absurd.

Like the Church in the Middle Ages, the current structures of the Churches in the Anglican Communion are incapable of healing the wound to Anglican faith and order. Even the Archbishop of Canterbury declared publicly, on the eve of GAFCON 2013, in the Cathedral of All Saints Nairobi, that the Instruments of the Anglican Communion are broken. The precedent of exigent circumstances suggests, again, the need for a genuine conciliar solution by Biblically faithful Anglicans. Please pray for such leaders within the Anglican Communion to rise up and do so—just as they did for the Church in the Middle Ages.

The Rev. Canon Phil Ashey is President & CEO of the American Anglican Council.

[1] Paul Avis, Beyond the Reformation: Authority, Primacy and Unity in the Conciliar Tradition (London: T&T Clark, 2008), at 72-73.

[2] Paul Avis, The Identity of Anglicanism: Essentials of Anglican Ecclesiology (London: Bloomsbury T&T Clark, 2008) at 9.

[3] Francis Oakley, The Conciliarist Tradition: Constitutionalism in the Catholic Church 1300-1870 (Oxford: OUP, 2003), at 39-40.