Source: International Update

(The following first appeared in the February 19, 2013 edition of the American Anglican Council’s International Update. Sign up for this free email here.)

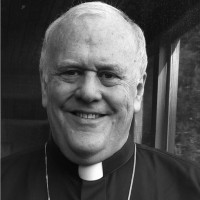

By Bishop Bill Atwood

My Ph.D. genius nephew works at an Ivy League bio-research lab. He has pet e-coli that he genetically mutates to get them to eat oil to help clean up oil spills. He has other ones that he programs to somehow become oil-I suppose to maintain the equilibrium on the planet.

Some of his colleagues are doing other research into cloning. Cloning is the process where snips and snails are mixed together with sugar and spice and new organisms emerge that are genetically linked to the donor snip and snail. In Scotland, geneticists cloned a sheep. In the Transylvanian mountains, in a dark lab embedded deep in a mountain, other ghoulish scientists are looking at a process to attempt to clone human beings.

When the limits of science are being pressed (and exceeded), I’m reminded of what Dr. Nephew says. “Just because you can do something doesn’t mean you should do it.”

His institution has a panel of ethicists who look at limits and morality. Inherent in the process is a sense of what a moral compass looks like. The church should be speaking to those issues. Decisions are made within the context of a moral framework. It was much easier when the framework was assumed to be the revealed truth of Biblical Christianity. As Western civilization moved away from that foundation, it has become increasingly problematic.

Any departure from the revealed truth of God’s Word is bad, but not all departures are equally bad. Some are just bad while others are really, really, really bad. How bad the impact is from a departure from revealed truth rises from a combination of how significant a decision is morally and how far from revealed truth the action goes.

For example, in the case of two similar moral acts which both depart from the same revealed truth, the one which is a further departure would be ethically “worse.” In the case of two different acts which have different moral weights, the one which is more “weighty” is of greater concern. This follows the Biblical pattern of glory. Glory, doxa, is a value assigned by God which is like the weightiness of gold. The more valuable something is to God, the more glory it has-the more weight it carries in the Kingdom.

A small departure from a critically important (or weighty) issue should generate more concern than a large departure from a trivial issue. Any departure from revealed truth will have consequences.

I’m proud of Dr. Nephew. His lab is doing everything they can to “get things right.” When they don’t know the moral answer, they don’t proceed. Others could learn from that, especially in dealing with decisions concerning weighty matters.

In the global struggle against terrorism, there are many complex areas. Life was in some ways easier when the assumed moral compass was Biblical Christianity. When the model was Biblical Christendom, it was also more faithful, even when the culture did not realize why decisions were being made the way they were.

Many of the assumptions of Biblical faith are still maintained, but the clear connection to Biblical faith has been lost. For example, advanced military schools like the USAF Air War College used to have classes in “Just War Theory.” The conversations were originally geared to help give a moral compass to soldiers who have to make life and death decisions on the battlefield. In the postmodern age, the idea that Christian faith might inform any action is repugnant to many people in pop culture, but it should not be so. Modern Western culture is very much “like it was in the days of Noah, where everyone did what was right in their own eyes.” Postmodernism has convinced people that every position is of equal weight morally, and that it is presumptuous to have confidence that one’s position is right. According to current social theory, my conviction of rightness should not have more weight than someone else’s. In this superficial and stupid fog, little attention is given to the consequences of erroneous belief or action.

A new value system has replaced revelation. It is an internal value system based on how something makes an individual feel. By this standard, something which makes me feel good is therefore right. Things begin to break down though because we live with others. At the same time something makes me feel good, it could make you feel bad. Then (by your definition) it would be wrong. In the postmodern construct, what makes me feel good at the moment is defined as good. Things that make me feel bad are designed as bad. Postmodernists overlook the fact that what an individual does impacts others.

The grievous failure of postmodernism me-ism is writ large in matters of life and death. It is evident in the abortion culture and in some of the emerging technologies of warfare. I’ve written about abortion before, but suffice it to say today that it has disastrous consequences. The other issue for today is the use of drones.

Drones are aircraft without pilots which are used for surveillance and precision attacks. Originally, the rationale behind their development was the ability to send aircraft into a hostile environment without putting a pilot at risk. Their use has been expanded because their abilities vastly exceed the capabilities of manned aircraft-at least in some ways. Their airborne endurance is much greater than that which is possible with human pilots on board. Strictly speaking, though, they are not really drones. A drone would be an autonomous machine that operates on its own. These are aircraft in which the pilot is not onboard, but is in a remote location and is flying by remote control. With the advent of technology, the capabilities of the mission that the “drones” fulfill has all of the precision that a manned aircraft can have, but the pilots can be rotated in the remote location so that missions can be much longer. Missions of twelve hours are not uncommon.

As technology developed, it became possible to observe events and personnel on the ground with great precision. With the use of infrared cameras and high precision radar, darkness is not even an obstacle. Eventually, armament was added to the airframe and it became possible to launch fire from missiles, guns, and bombs with the pilot being ten thousand miles away. These Unmanned Aerial Vehicles (UAVs) have proliferated, especially in the Middle East where there are vast areas in which hostile forces live in abundance.

The use of UAV became increasingly popular with some military strategists and counter insurgency forces because of the ability to penetrate deep into hostile territory. The loss of an expensive machine is not as serious as the loss of a human pilot. Additionally, the capture of a human pilot poses terrible problems of exploitation, torture, and international embarrassment, not to mention the impact on the human pilot.

UAVs have been particularly popular with some military leaders because of their ability to loiter and target individuals. This, however, raises some terrible problems. Where the strategy used to be an attempt to capture terrorists, drones do not provide that possibility. With the drone, subjects can be observed or killed. They cannot be captured. This is a great concern for a host of reasons. First there are-or at least should be-great limits put on the use of lethal force. Many ethicists have allowed for the possibility of just war, but lethal force was only used as a last resort. Now, with drones, there are only two possibilities: observation and death. Christian ethics should be speaking directly to this issue, bringing the values of the Kingdom to bear. I do not think it is essential for Christians to be pacifists, but we must live and act responsibly and in accordance with the guidance of revelation of the Word of God.

Though fewer forces are put at risk in using the pilotless surveillance aircraft to observe and attack terrorists, the fact that none are captured is significant. Terrorists who have been killed cannot be a source of intelligence about attacks that are being planned. Drone attacks have been so expanded there is hardly any intelligence being garnered from captured terrorists.

Even with the precision of the weapons there is another huge problem. That is what is euphemistically called “collateral damage.” What that refers to are casualties (injury or death) of those who are in the vicinity of the targeted person. Even with high confidence in the accuracy of identifications, aerial based recognition cannot be as certain as a face-to-face encounter can be. There are multiple problems that are very serious. The first is the possibility of misidentification. When lethal force is being used, mistakes cannot be corrected. It is also inadequate to say that it is all right to target a known terrorist when there are others in the vicinity who may be innocent. The fact that strategists “really want” to eliminate a known terrorist is not sufficient cause to take innocent lives at the same time.

There is another factor. That is the ambience of combat. Even when the technology is meticulously designed to provide a range of information, it is not the same thing to sit in a bunker with flight controls, as it is to be in harm’s way in combat. It seems to me that the awareness of the soldier (or airman) who is actually in the combat zone adds to the sense of gravity about the weight of what is happening and what is being contemplated in the use of force. There is a disconnect when someone can be targeted lethally and the ones doing the targeting cannot even be identified, much less harmed.

Philosophically, these issues need to be addressed by the church. We need to be challenging those who make decisions of life and death to consider the ethical implications. I am not suggesting that a posture of pacifism must be adopted by nations. Given the great hostilities that exist in the world today, that is impractical. It could even be wrong. But I am suggesting that the church needs to be involved in speaking to the issues and holding people accountable. Where the issues are complex and the consequences are unknown, we could learn something from Dr. Nephew. “Just because you can do something doesn’t mean you should.”

Bishop Bill Atwood is Bishop of the International Diocese in the Anglican Church in North America